罗伯特·沃尔丁格TED演讲:美好人生的幸福来源

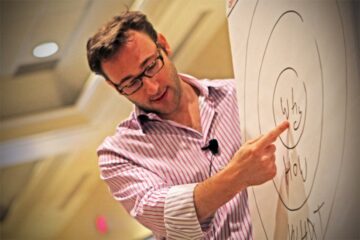

什么是真正美好的生活?哈佛大学成人发展研究负责人罗伯特·沃尔丁格(Robert Waldinger)博士在其轰动全球的TED演讲中,给出了一个颠覆常规的答案。作为史上最长历时75年的纵向研究第四代负责人,罗伯特·沃尔丁格通过追踪724位男性的真实人生轨迹,揭示了美好人生的幸福来源并非财富、名望或成就,而是高质量的人际关系。

这项跨越三代人的研究发现:

1️⃣ 孤独对健康有害,而良好的人际连接显著提升生活满意度和身体健康;

2️⃣ 关系的质量远比数量重要,温暖稳定的亲密关系能缓冲生活压力、延缓衰老;

3️⃣ 幸福不在于社交广度而在于深度,即使只有少数知己也能带来巨大满足。

罗伯特·沃尔丁格(Robert Waldinger) 是美国哈佛大学医学院的精神病学临床教授,同时也是哈佛成人发展研究(Harvard Study of Adult Development) 的现任主任。这项研究是迄今为止历时最长的关于成人生活的纵向研究之一。他在TED演讲中强调:“那些在50岁时对人际关系最满意的人,在80岁时也是最健康的。” 这一结论打破了“成功即幸福”的迷思,直指美好人生的幸福来源本质——投入时间和精力构建深层情感联结,才是人生最明智的投资。

以下是罗伯特·沃尔丁格TED演讲《What makes a good life:美好人生的幸福来源》中英对照文本:

| What keeps us healthy and happy as we go through life? | 在我们的人生中,是什么让我们保持健康且幸福呢? |

| If you were going to invest now in your future best self, where would you put your time and your energy? | 如果现在你可以为未来的自己投资,你会把时间和精力投资在哪里呢? |

| There was a recent survey of millennials asking them what their most important life goals were, | 最近在千禧一代中有这么一个调查,问他们生活中最重要的目标是什么, |

| and over 80 percent said that a major life goal for them was to get rich. | 超过80%的人说最大的生活目标就是要有钱。 |

| And another 50 percent of those same young adults said that another major life goal was to become famous. | 还有50%的年轻人说另一个重要的生活目标就是要出名。 |

| And we’re constantly told to lean in to work, to push harder and achieve more. | 而且我们总是被灌输要投入工作,要加倍努力,要成就更多。 |

| We’re given the impression that these are the things that we need to go after in order to have a good life. | 我们被灌输了这样一种观念,只有做到刚才说的这些才能有好日子过。 |

| Pictures of entire lives, of the choices that people make and how those choices work out for them, | 要人们纵观整个人生,想象各种选择,以及这些选择最终导致的结果, |

| those pictures are almost impossible to get. | 几乎是不可能的。 |

| Most of what we know about human life we know from asking people to remember the past, | 关于人的一生,我们能了解到的大部分都是通过人的回忆得来, |

| and as we know, hindsight is anything but 20/20. | 但众所周知,大部分都是事后诸葛。 |

| We forget vast amounts of what happens to us in life, and sometimes memory is downright creative. | 一生中,我们会忘记很多发生过的事情,而且记忆常常不可靠。 |

| But what if we could watch entire lives as they unfold through time? | 但如果我们可以从头到尾地纵观人的一生呢? |

| What if we could study people from the time that they were teenagers all the way into old age | 如果我们可以跟踪研究一个人,从他少年时代开始一直到他步入晚年, |

| to see what really keeps people happy and healthy? | 看看究竟是什么让人们保持快乐和健康呢? |

| We did that. The Harvard Study of Adult Development may be the longest study of adult life that’s ever been done. | 我们做到了。哈佛大学(进行的)这项关于成人发展的研究,可能是同类研究中耗时最长的。 |

| For 75 years, we’ve tracked the lives of 724 men, year after year, | 在75年的时间里,我们跟踪了724个人的一生,年复一年, |

| asking about their work, their home lives, their health, | 了解他们的工作、家庭生活、健康状况, |

| and of course asking all along the way without knowing how their life stories were going to turn out. | 当然,在这一过程中,我们完全不知道他们的人生将走向何方。 |

| Studies like this are exceedingly rare. | 像这样的研究少之又少。 |

| Almost all projects of this kind fall apart within a decade because too many people drop out of the study, | 像这样的项目几乎都会在10年内终止,因为有许多人会中途退出, |

| or funding for the research dries up, or the researchers get distracted, or they die, | 或者是研究资金不足,或者是研究者转换方向,或者去世, |

| and nobody moves the ball further down the field | 然后项目无人接手。 |

| But through a combination of luck and the persistence of several generations of researchers, this study has survived. | 但感谢幸运女神的眷顾和几代研究人员的坚持不懈,这个项目存活下来了。 |

| About 60 of our original 724 men are still alive, still participating in the study, most of them in their 90s. | 目前这724人中仍有60人在世,仍然在参与研究大多数人已经90多岁了。 |

| And we are now beginning to study the more than 2,000 children of these men. | 现在我们已经开始研究他们的子孙后代,人数多达2000多人。 |

| And I’m the fourth director of the study. | 我是这个项目的第四任负责人。 |

| Since 1938, we’ve tracked the lives of two groups of men. | 从1938年起,我们开始跟踪两组人的生活。 |

| The first group started in the study when they were sophomores at Harvard College. | 第一组加入这个项目的人,当年在哈佛大学上大二。 |

| They all finished college during World War II, and then most went off to serve in the war. | 他们在二战期间大学毕业,大部分人都参军作战了。 |

| And the second group that we’ve followed was a group of boys from Boston’s poorest neighborhoods, | 我们追踪的第二组人是一群来自波士顿贫民区的小男孩, |

| boys who were chosen for the study specifically | 他们之所以被选中, |

| because they were from some of the most troubled and disadvantaged families in the Boston of the 1930s. | 主要是因为他们来自20世纪30年代波士顿最困难最贫困的家庭。 |

| Most lived in tenements, many without hot and cold running water. | 大部分住在廉价公寓里,很多都没有冷热水供应。 |

| When they entered the study, all of these teenagers were interviewed. | 在加入这个项目时,这些年轻人都接受了面试。 |

| They were given medical exams. We went to their homes and we interviewed their parents. | 接受了身体检查。我们挨家挨户走访了他们的父母。 |

| And then these teenagers grew up into adults who entered all walks of life. | 然后这些年轻人长大成人,进入到社会各个阶层。 |

| They became factory workers and lawyers and bricklayers and doctors, one President of the United States. | 成为了工人、律师、砖匠、医生,还有一位成了美国总统。 |

| Some developed alcoholism. A few developed schizophrenia. | 有人成为酒鬼,有人患了精神分裂。 |

| Some climbed the social ladder from the bottom all the way to the very top, | 有人从社会最底层一路青云直上, |

| and some made that journey in the opposite direction. | 也有人恰相反,掉落云端。 |

| The founders of this study would never in their wildest dreams have imagined that | 这个项目的创始人们,可能做梦都不会想到 |

| I would be standing here today, 75 years later, telling you that the study still continues. | 75年后的今天,我会站在这里,告诉你们这个项目还在继续。 |

| Every two years, our patient and dedicated research staff calls up our men | 每两年,我们耐心而专注的研究人员会打电话给我们的研究对象, |

| and asks them if we can send them yet one more set of questions about their lives. | 问他们是否愿意再做一套关于他们生活的问卷。 |

| Many of the inner city Boston men ask us, | 那些来自波士顿的人问我们, |

| “Why do you keep wanting to study me? My life just isn’t that interesting.” | “为什么你们一直想研究我?我的生活是很无趣的。” |

| The Harvard men never ask that question. | 但哈佛的人从没这样问过。 |

| To get the clearest picture of these lives, we don’t just send them questionnaires. | 为了更好地了解这些人的生活,我们不光给他们发问卷。 |

| We interview them in their living rooms. We get their medical records from their doctors. | 我们还在他们家客厅采访他们。从他们医生那儿拿病历。 |

| We draw their blood, we scan their brains, we talk to their children. | 抽他们的血,扫描他们的大脑,跟他们的孩子聊天。 |

| We videotape them talking with their wives about their deepest concerns. | 我们拍摄下他们和妻子谈话的场景,聊的都是他们最关心的问题。 |

| And when, about a decade ago, we finally asked the wives if they would join us as members of the study, | 大约在10年前,我们终于开口问他们的妻子,是否愿意加入我们的研究, |

| many of the women said, “You know, it’s about time.” | 很多女士都说,“是啊,终于轮到我们了。” |

| So what have we learned? | 那么我们得到了什么结论呢? |

| What are the lessons that come from the tens of thousands of pages of information that we’ve generated on these lives? | 那长达几万页的数据记录,记录了他们的生活,我们从这些记录中间,到底学到了什么? |

| Well, the lessons aren’t about wealth or fame or working harder and harder. | 不是关于财富、名望,或更加努力工作。 |

| The clearest message that we get from this 75-year study is this: | 从75年的研究中,我们得到的最明确的结论是: |

| Good relationships keep us happier and healthier. Period. | 良好的人际关系能让人更加快乐和健康。就这样。 |

| We’ve learned three big lessons about relationships. | 关于人际关系,我们得到三大结论。 |

| The first is that social connections are really good for us, and that loneliness kills. | 第一,社会关系对我们是有益的,而孤独寂寞有害健康。 |

| It turns out that people who are more socially connected to family, to friends, to community, | 我们发现,那些跟家庭成员更亲近的人,更爱与朋友、与邻居交往的人, |

| are happier, they’re physically healthier, and they live longer than people who are less well connected. | 会比那些不善交际、离群索居的人,更快乐,更健康,更长寿。 |

| And the experience of loneliness turns out to be toxic. | 孤独寂寞是有害健康的。 |

| People who are more isolated than they want to be from others find that they are less happy, | 那些“被孤立”的人,跟不孤单的人相比,往往更加不快乐, |

| their health declines earlier in midlife, their brain functioning declines sooner | 等他们人到中年时,健康状况下降更快,大脑功能下降得更快, |

| and they live shorter lives than people who are not lonely. | 也没那么长寿。 |

| And the sad fact is that at any given time, more than one in five Americans will report that they’re lonely. | 可惜的是,长久以来,每5个美国人中就至少有1个声称自己是孤独的。 |

| And we know that you can be lonely in a crowd and you can be lonely in a marriage, | 而且即便你身在人群中,甚至已经结婚了,你还是可能感到孤独, |

| so the second big lesson that we learned is that it’s not just the number of friends you have, | 因此我们得到的第二大结论是不是你有多少朋友, |

| and it’s not whether or not you’re in a committed relationship, | 也不是你身边有没有伴侣, |

| but it’s the quality of your close relationships that matters. | 真正有影响的是这些关系的质量。 |

| It turns out that living in the midst of conflict is really bad for our health. | 整天吵吵闹闹对健康是有害的。 |

| High-conflict marriages, for example, without much affection, | 比如成天吵架,没有爱的婚姻, |

| turn out to be very bad for our health, perhaps worse than getting divorced. | 对健康的影响或许比离婚还大。 |

| And living in the midst of good, warm relationships is protective. | 而关系和睦融洽,则对我们的健康有益。 |

| Once we had followed our men all the way into their 80s, we wanted to look back at them at midlife | 当我们的研究对象步入80岁时,我们会回顾他们的中年生活, |

| and to see if we could predict who was going to grow into a happy, healthy octogenarian and who wasn’t. | 看我们能否预测哪些人会在八九十岁时过得快乐、健康,哪些人不会。 |

| And when we gathered together everything we knew about them at age 50, | 我们把他们50岁时的所有信息进行汇总分析, |

| it wasn’t their middle age cholesterol levels that predicted how they were going to grow old. | 发现决定他们将如何老去的,并不是他们中年时的胆固醇水平。 |

| It was how satisfied they were in their relationships. | 而是他们对婚姻生活的满意度。 |

| The people who were the most satisfied in their relationships at age 50 were the healthiest at age 80. | 那些在50岁时满意度最高的人,在80岁时也是最健康的。 |

| And good, close relationships seem to buffer us from some of the slings and arrows of getting old. | 另外,良好和亲密的婚姻关系能减缓衰老带来的痛苦。 |

| Our most happily partnered men and women reported, in their 80s, | 参与者中那些最幸福的夫妻告诉我们,在他们80多岁时, |

| that on the days when they had more physical pain, their mood stayed just as happy. | 哪怕身体出现各种毛病,他们依旧觉得日子很幸福。 |

| But the people who were in unhappy relationships, | 而那些婚姻不快乐的人, |

| on the days when they reported more physical pain, it was magnified by more emotional pain. | 身体上会出现更多不适,因为坏情绪把身体的痛苦放大了。 |

| And the third big lesson that we learned about relationships and our health is that | 关于婚姻和健康的关系,我们得到的第三大结论是, |

| good relationships don’t just protect our bodies, they protect our brains. | 幸福的婚姻不单能保护我们的身体,还能保护我们的大脑。 |

| It turns out that being in a securely attached relationship to another person in your 80s is protective, | 研究发现,如果在80多岁时,你的婚姻生活还温暖和睦, |

| that the people who are in relationships where they really feel they can count on the other person in times of need, | 你对自己的另一半依然信任有加,知道对方在关键时刻能指望得上, |

| those people’s memories stay sharper longer. | 那么你的记忆力都不容易衰退。 |

| And the people in relationships where they feel they really can’t count on the other one, | 而反过来,那些觉得无法信任自己的另一半的人, |

| those are the people who experience earlier memory decline. | 记忆力会更早表现出衰退。 |

| And those good relationships, they don’t have to be smooth all the time. | 幸福的婚姻,并不意味着从不拌嘴。 |

| Some of our octogenarian couples could bicker with each other day in and day out, | 有些夫妻,八九十岁了,还天天斗嘴, |

| but as long as they felt that they could really count on the other when the going got tough, | 但只要他们坚信,在关键时刻,对方能靠得住, |

| those arguments didn’t take a toll on their memories. | 那这些争吵顶多只是生活的调味剂。 |

| So this message, that good, close relationships are good for our health and well-being, | 所以请记住,幸福和睦的婚姻对健康是有利的, |

| this is wisdom that’s as old as the hills. | 这是永恒的真理。 |

| Why is this so hard to get and so easy to ignore? Well, we’re human. | 但为什么我们总是办不到呢?因为我们是人类。 |

| What we’d really like is a quick fix, something we can get that’ll make our lives good and keep them that way. | 我们总喜欢找捷径,总想一劳永逸,找到一种方法解决所有问题。 |

| Relationships are messy and they’re complicated and the hard work of tending to family and friends, | 人际关系麻烦又复杂,与家人、朋友相处需要努力付出, |

| it’s not sexy or glamorous. It’s also lifelong. It never ends. | 一点也不高大上。而且需要一辈子投入,无穷无尽。 |

| The people in our 75-year study who were the happiest in retirement | 在我们长达75年的研究中,那些最享受退休生活的人, |

| were the people who had actively worked to replace workmates with new playmates. | 是那些主动用玩伴来替代工作伙伴的人。 |

| Just like the millennials in that recent survey, | 就像开头我说过的千禧一代一样, |

| many of our men when they were starting out as young adults really believed that | 我们跟踪研究的很多人在年轻的时候坚信 |

| fame and wealth and high achievement were what they needed to go after to have a good life. | 名望、财富和成就是他们过上好日子的保证。 |

| But over and over, over these 75 years, our study has shown that the people who fared the best | 但在75年的时间里,我们的研究一次次地证明,日子过得最好的, |

| were the people who leaned in to relationships, with family, with friends, with community. | 是那些主动与人交往的人,与家人、朋友或者邻居。 |

| So what about you? Let’s say you’re 25, or you’re 40, or you’re 60. | 那么你们呢?也许你现在25岁,或者40岁,或者60岁。 |

| What might leaning in to relationships even look like? | 怎样才算主动与人交往呢? |

| Well, the possibilities are practically endless. | 嗯,我想有很多种方法吧。 |

| It might be something as simple as replacing screen time with people time | 最简单的,别再跟屏幕聊天了,去跟人聊天, |

| or livening up a stale relationship by doing something new together, long walks or date nights, | 或者一起尝试些新事物,让关系恢复活力,一起散个步呀,晚上约个会呀, |

| or reaching out to that family member who you haven’t spoken to in years, | 或者给多年未曾联系的亲戚打个电话, |

| because those all-too-common family feuds take a terrible toll on the people who hold the grudges. | 因为这种家庭不和睦太常见了,但它带来的伤害又很大,尤其对那些喜欢生闷气的人来说更是如此。 |

| I’d like to close with a quote from Mark Twain. | 我想引用马克·吐温的一段话来作为结束。 |

| More than a century ago, he was looking back on his life, and he wrote this: | 一个多世纪前,他回首自己的人生,写下这样一段话: |

| “There isn’t time, so brief is life, for bickerings, apologies, heartburnings, callings to account. | “时光荏苒,生命短暂,别将时间浪费在争吵、道歉、伤心和责备上。 |

| There is only time for loving, and but an instant, so to speak, for that.” | 用时间去爱吧,哪怕只有一瞬间,也不要辜负。” |

| The good life is built with good relationships. Thank you. | 美好人生,从良好的人际关系开始。谢谢大家。 |

声明:本站所有文章,如无特殊说明或标注,均为绝学社原创发布。任何个人或组织,在未征得本站同意时,禁止复制、盗用、采集、发布本站内容到任何网站、书籍等各类媒体平台。如若本站内容侵犯了原著者的合法权益,可联系绝学社网站管理员进行处理。