大家好,我想在周中给大家带来一点小小的特别节目。我一直觉得简·奥斯汀令人着迷的,不仅仅是她小说中的闪光点,还有她自己的生命经历如何在其作品深处静静回响。读她的书时,你会有这样一种感觉:她并非完全凭空创造一切。她是在反思她所熟悉的事物——她拜访过的房屋、可能感受过的家庭紧张关系、尴尬的舞会、错失的机会,当然,也有那些微小的胜利。

首先要说明的是,我并非在此宣称发现了确凿的证据或绝对的真理。这里的许多内容关乎共鸣。有些事实是清晰的,尤其是当我们可以将其与她现存的书信对应起来时。而另一些则更侧重于相似性,即她小说中那些令人不禁怀疑是否源自自身经历的片段。作为读者,我们总会忍不住去想,这些平行相似之处是作者有意为之,还是仅仅是生活自然渗入艺术的結果。

甚至奥斯汀本人也偶尔会流露出其作品的个人色彩。在1813年写给姐姐卡桑德拉的信中,她称《傲慢与偏见》为“我亲爱的孩子”。这是一句随口的话,一如既往地带着戏谑,但它告诉我们一些重要的信息:她将小说视作自己的一部分,不是抽离的创造物,而是她自身形象、或许也是她自身生活的映照。简在描述收到第一本《傲慢与偏见》时写道:“我想告诉你,我从伦敦得到了我亲爱的孩子。星期三,我收到了福克诺寄来的一本,亨利附了三行字说他已经给了查尔斯一本,并通过马车寄了第三本去戈默舍姆。”

所以,在本期视频中,我想探索这些共鸣,将简·奥斯汀的生活与她的虚构作品并置,留意那些界限可能模糊的地方。伊丽莎白·班纳特的机智是否回响着简自己的声音?巴顿小屋是否是乔顿小屋的翻版?安妮·埃利奥特那份静静的遗憾是否也是奥斯汀的?我不能承诺给你们确切的答案,但我可以承诺带你们踏上一段旅程,穿越其中一位有史以来最敏锐的头脑所展现的反讽、挫折与观察——这位头脑曾拿起笔,或者我们说,羽毛笔。

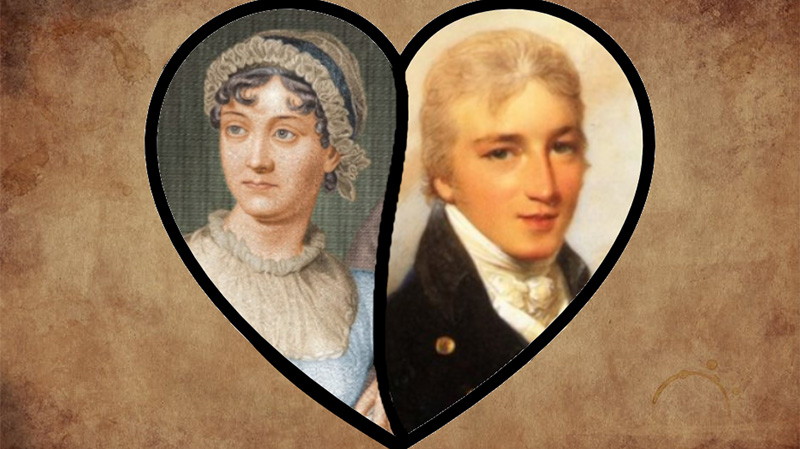

如果有一个领域,奥斯汀的真实生活与小说仿佛在默契地相互致意,那便是爱情。我们知道她自己也经历过几段浪漫插曲,有些轻松愉快,有些认真投入,有些或许颇为尴尬。

以汤姆·勒弗罗伊为例。他是简密友的侄子,两人相识于1795年。她写信告诉卡桑德拉,“几乎不敢告诉你我和我的爱尔兰朋友是怎么相处的”。字里行间充满她一贯的反讽。但事实上,他们一起跳舞、调情,她也承认他非常讨人喜欢。然而,正如伊丽莎白·班纳特与达西先生的对峙一样,社会现实介入其中。勒弗罗伊的家人反对这段关系。简没有财产,这段恋情就此夭折。在小说里,伊丽莎白克服万难赢得了心上人。在现实中,简没有。

还有哈里斯·比格-威瑟,他在1802年向简求婚,她接受了,但第二天早晨就改变了主意。这真是一个女主角才会做的举动。完全是迷你版的爱玛·伍德豪斯。她有信心对一个富有、务实、本可以保障她未来的男人说不,只因为她无法忍受与他在一起的想法。她笔下的女主角们也常常拥有同样的勇气:伊丽莎白拒绝柯林斯先生,安妮·埃利奥特解除与温特沃斯上校的婚约。这些拒绝的举动都承载着真实的风险,正如简自己所做的那样。

但最让我着迷的是其中的反讽。在她的小说中,拒绝总是会得到更好的回报:真爱、幸福结局、那个对的人。而在简自己的生活中,拒绝留给她的却是自由,以及不确定性、对家庭的依赖和“老处女”这个挥之不去的标签。人们很容易将她的女主角们看作是她对另一种人生的想象:如果世界更友善一点,或者如果她的勇气换来的是幸运而非挫败,那又会怎样?

所以,当伊丽莎白·班纳特调侃达西时,或者当安妮·埃利奥特最终得到第二次机会时,我不禁觉得,简是在让她的女主角们活出她自己被剥夺的结局。

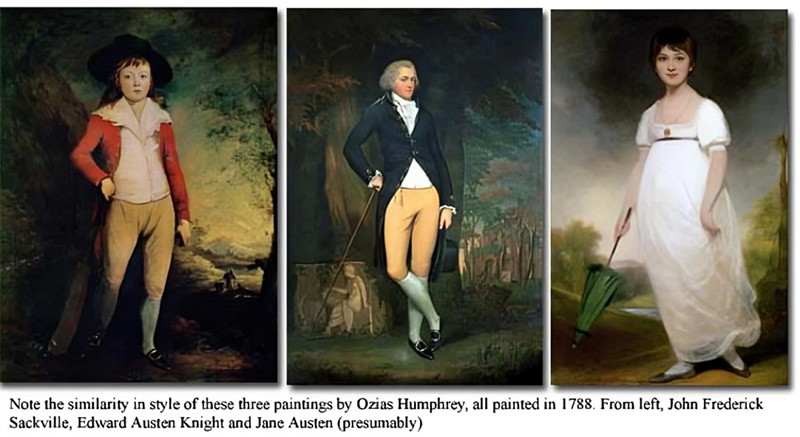

如果奥斯汀的爱情故事暗示了她个人的渴望,那么她的家庭关系则揭示了她一些最深的挫折。这一点在她哥哥爱德华·奈特的故事中体现得最为明显。

爱德华是幸运的那个。他被富有的表亲收养,继承了在肯特郡和汉普郡的大片地产,过着乡绅的生活。而在他们的父亲于1805年去世后,简、卡桑德拉和她们的母亲却陷入了远不稳定得多的境地。她们依靠亲戚接济,从巴斯搬到南安普顿,从未真正安定下来,当然也谈不上舒适或独立。

后来,爱德华确实为她们提供了帮助。1809年,他将自己汉普郡庄园附近那所简朴的乔顿小屋提供给了她们。这里成了简永久的家,也是她创作出那些伟大小说的地点。但她们花了四年时间才走到这一步。为什么?部分原因似乎是乔顿小屋不能立即入住。租户必须搬走后,爱德华才能提供它。所以公平地说,这可能不完全是拖延。

尽管如此,其中的反讽难以忽视。爱德华极其富有,而她的姐妹和母亲则不然。即使小屋暂时空不出来,他本可以更早、更慷慨地资助她们。用现代的眼光看,这份援助来得晚了。

而这里,生活与小说似乎再次相互呼应。在《理智与情感》中,达什伍德母女们的家产被继承人约翰·达什伍德和他时髦的妻子范妮夺走。善意的承诺化作了象征性的表示,达什伍德一家被劝进了一间更小的、需要依靠亲戚的乡舍。小说中的巴顿小屋与现实中的乔顿小屋惊人地相似:次优但实用。

当然,我们无法证明爱德华和他的妻子伊丽莎白就是简笔下约翰和范妮·达什伍德的原型,但其中的相似之处引人注目。人们不禁会想,当爱德华和伊丽莎白在1811年读到《理智与情感》时(假设他们读了),他们是否在书页中瞥见了自己的影子?如果真是这样,简从未承认过。但以我对她的了解,我宁愿认为她乐在其中,享受着这种反讽。

因此,乔顿小屋既是依赖的象征,也是奥斯汀创作自由的基石。正如她笔下虚构的达什伍德一家在巴顿小屋安之若素,简也将这所次优的房子变成了流传数个世纪的文学的诞生地。

如果说奥斯汀的家庭赋予了她故事情感的支柱,那么她居住和游览过的地方则为其提供了背景。我们一次又一次地看到她将真实环境重新想象到小说中,有时满怀深情,有时则带着犀利的讽刺。

以巴斯为例。当奥斯汀一家于1801年搬到那里时,它被认为是上流社会的时尚中心,一个看人与被看的地方。但简从未真正喜欢过那里。在她的信中,她抱怨拥挤的聚会和无聊的派对,你能感觉到她觉得整个婚姻市场的氛围有点令人疲惫。

在《诺桑觉寺》中,巴斯成了凯瑟琳·莫兰天真冒险的背景板——起初令人兴奋,但也流于肤浅,充满了空虚的闲聊和虚伪的友谊。当然,在多年后写成的《劝导》中,巴斯被描绘得更加尖锐。它是安妮·埃利奥特感到最为失意的地方,被困在一个注重表象而非实质的城市里。换句话说,巴斯是奥斯汀基于自身复杂经历对社会表演性所作的评论。

还有莱姆里吉斯(Lyme Regis)。1804年,简游览了这个海滨小镇,她的信中提到那戏剧性的 Cobb 堤墙、优美的悬崖和湿滑台阶的危险。这些细节精准地重现于《劝导》中,路易莎·马斯格罗夫在Cobb堤上的戏剧性跌落改变了小说的进程。这是其中一个时刻,旅行日记和虚构小说之间的界限几乎消失了。

我们也不能忘记那些大宅邸。通过哥哥爱德华,简曾在肯特郡的戈默舍姆度过时光,那是一处拥有广阔庭院和乡绅所有配件的正规庄园。你可以在《傲慢与偏见》中罗辛斯庄园的宏伟,或《爱玛》中唐威尔 Abbey 的舒适优雅中感受到它的影子。简亲身了解过作为客居于此等宅邸意味着什么:既享受其壮丽,又敏锐地意识到其间构筑生活的社会鸿沟。

在所有这些例子中,令我印象深刻的是奥斯汀如何改造这些地点。巴斯不仅仅是一座城市,它是一个虚荣的舞台。莱姆不仅仅是一个海滨度假胜地,它是激情与危险的场所。而那些大宅邸也不仅仅是漂亮的布景,它们是财富、权力和社会失衡的象征。她汲取所见,并将其锐化,直到每个地方都变得既真实又富有隐喻。

因此,每当我们漫步于《诺桑觉寺》中的巴斯,或《劝导》中的Cobb堤,或坐在罗辛斯庄园的 drawing room 时,我们实际上正与简·奥斯汀本人一同穿行于她所熟知的地方,这些地方经过她小说的折射,既熟悉又被转化了。

如果你真想一窥小说背后的那位小说家,你必须去读简·奥斯汀的信件。不是那些被卡桑德拉销毁的信——可惜有成百上千封就此遗失——而是那些幸存下来的。它们向我们呈现了最不加过滤的简:机智、爱说闲话、犀利,且常常毫不留情。

引人注目的是,这些信件的语气感觉就像是她小说创作的DNA。例如,在1796年,她描述一位邻居“太高太壮,谈不上有任何优雅”。这是一句随口的话,但其节奏感与她的人物素描如出一辙。你几乎能听到埃尔顿太太或沃尔特·埃利奥特爵士从书页中走出来。

她对时尚同样苛刻。在另一封信中,她嘲笑一位年轻女子穿着不得体而显得“非常平庸”——这种评论在她写的每一个舞会场景中都会重现。她对礼仪也能很尖刻。一位相识者的“礼仪不太有世故之气”。这句话简直可以直接走进《爱玛》。

还有旅行见闻。当简游览莱姆里吉斯时,她描述了Cobb墙和石阶湿滑的危险。几年后,路易莎·马斯格罗夫当然就在《劝导》中发生了她那出了名的跌落。你几乎可以直接从她的信件追溯到完成的场景。

令我着迷的是,这些信件本非为世人所写。它们是写给卡桑德拉或她的侄女们的,从未想过出版。然而其中的机智、反讽、极其敏锐的观察力都跃然纸上。仿佛她的私人通信是她的素描本,是她打磨声音、测试幽默感、练习将生活转化为人物艺术的地方。

当然,人们很容易将这些信件视为一种坦白——奥斯汀向我们展示她小说的原材料。但或许更准确的说法是,信件和小说都源于同一个地方:她对人们无尽的好奇心、她对反讽的喜爱,以及看穿矫饰的天赋。

所以,当我们读到凯瑟琳·德·伯尔夫人盛气凌人地教训伊丽莎白·班纳特,或埃尔顿太太吹嘘她的“资源”,甚至沃尔特·埃利奥特爵士欣赏自己的倒影时,我们读到的不仅仅是小说。我们听到的,正是简在信中使用的同一个声音:犀利、俏皮,还有一点点刻薄。

如果有一个问题读者们不断回归,那就是:我们在她的女主角身上能找到多少简·奥斯汀自己的影子?我认为,答案既复杂,又比初看起来更发人深省。

以《理智与情感》中的埃莉诺·达什伍德为例。她是克制、耐心和坚韧的化身,默默维系着家庭,同时自己承受着失望。在简身上也有这种稳重,尤其是在她父亲去世后那些经济不确定的岁月里,那时她和卡桑德拉不得不依靠兄弟的施舍。

还有伊丽莎白·班纳特:机智、坦率、不愿没有感情地结婚。很难不将简·奥斯汀自己犀利的智慧映射到伊丽莎白的妙语连珠上。伊丽莎白拒绝柯林斯先生,也映射了简自己拒绝哈里斯·比格-威瑟——即使社会期望她答应,她也有勇气说不。

《劝导》中的安妮·埃利奥特则更为忧郁。小说开始时她27岁,被认为“错过了花期”,被放弃初恋的遗憾所困扰。在这里,我们或许也能听到简自己的回响——她到了那个年纪时,同样拒绝了一段安稳的婚姻,并悄然地意识到自己的机会正在变窄。安妮与温特沃斯上校的第二次机会,几乎像是简希望得到却从未收到的礼物。

然后是爱玛·伍德豪斯:自信的媒人,安稳于其财富和地位。爱玛可能是离简现实生活最远的一个,但或许最接近她的想象。爱玛代表了一种独立的生活,一个女人可以插手、谋划、犯错,而她的整个存在不必依赖于丈夫的财富。如果伊丽莎白是简的机智,安妮是她的遗憾,那么爱玛可能就是她的愿望满足——一个拥有简自己从未有过的自由的女主角。

那么,这些女主角是自传性的吗?不完全是。她们都是简·奥斯汀的不同侧面:她的耐心、她的机智、她的失望、她的渴望。在塑造她们时,她不仅仅是在讲述别人的故事。她是在将自己的生活折射进小说,以微妙而深刻的方式将自己散落在作品的各个角落。

这或许就是为什么她的女主角至今仍让我们感觉如此鲜活。因为通过她们,我们读到的不仅仅是埃莉诺、伊丽莎白、安妮或爱玛。我们听到的是简·奥斯汀的多种声音。

那么,我们看到了什么?简·奥斯汀的小说并非在真空中写就。它们回响着她自身生活的余音:她 卖弄风骚而又拒绝过的浪漫情事、家庭依赖带来的挫折、她居住过和不喜欢的地方,以及最重要的,在她信件中闪耀的机智与反讽。

但奥斯汀并非简单地将生活复制到书页上;她改造了它。失望变成了喜剧。限制变成了讽刺。她的女主角成了她可以借此探索自身愿望、遗憾、甚至她想象中的自由的代言人。伊丽莎白的反抗、安妮的忧郁、爱玛的独立——她们都承载着简自己的一部分,经过折射和重塑,直到虚构与现实交融在一起。

也许这就是她的小说历久弥新的原因。它们不仅仅是爱情故事或风俗喜剧。在某种意义上,它们是简·奥斯汀试图描绘她所知的世界的努力——有时忠实,有时反讽,也许有时如同她所希望的那样。

在我结束之前,我想引用一下我收到的一个很棒的建议,来自 J Dylan 3035,我现在把它放在屏幕上给大家看。她说:

“为了给您的视频来个有趣的转折,您能不能做一期节目,询问您的女性观众她们最认同奥斯汀笔下的哪个角色,以及她们可能会选择谁做最好的朋友?对于男性听众,奥斯汀的女主角中最吸引你的是谁?”

我认为这是个绝妙的主意,我很想听听你们的想法。所以,显然在下面评论吧,好吗?奥斯汀的角色中,你在谁身上看到了自己?谁会是你的密友?或者也许全面考虑,包括她的男性角色?如果你感觉大胆,你会为谁倾心?

因为归根结底,奥斯汀的小说关乎连接——关乎在我们自己、我们的朋友、甚至我们的家人中,看到她所创造的角色。如果简·奥斯汀能将她自己的生活编织进她的小说里,那么我们当然也能将一点点我们自己编织进我们对她作品的阅读中。

这值得思考,我确信。

本期内容就到这里。

Hi everyone. I thought I’d give you a little midweek extravaganza.

What I’ve always found fascinating about Jane Austen isn’t just the sparkle of her novels, but the way her own life seems to hum quietly beneath the surface of them. You get the sense reading her that she isn’t quite conjuring everything up from thin air. She’s reflecting on what she knew, the houses she visited, the family tensions she might have felt, the awkward dances, and the missed chances, as well as the little triumphs, too.

Now, I should say straight away, I’m not claiming to uncover hard evidence or absolute truths here. Much of this is about resonance. Some things are clear, especially when we can anchor them to her surviving letters. Others are more a matter of likeness, moments in her fiction that feel suspiciously close to her own experiences. And as readers, we can’t help but wonder if these parallels are intentional or simply a natural seepage of life into art.

Even Austen herself occasionally lets slip just how personal her work was. In her letters to her sister Cassandra in 1813, she called Pride and Prejudice “My Darling Child.” It’s a throwaway remark, playful as ever, but it tells us something important. She thought of her novels as part of herself, not detached creations, but reflections of her own image and perhaps her own life. Jane described receiving her first copies of Pride and Prejudice: “I want to tell you that I’ve got my own darling child from London. On Wednesday, I received one copy sent down by Falknor with three lines from Henry to say that he had given another to Charles and sent a third by the coach to Godmersham.”

So, in this video, I want to explore those resonances to place Jane Austen’s life alongside her fiction and notice where the lines perhaps blur. Did Elizabeth Bennett’s wit echo Jane’s own? Was Barton Cottage a version of Chawton? Was Anne Elliot’s quiet regret Austen’s as well? Now, I can’t promise you definitive answers, but I can promise you a journey through the ironies, the frustrations, and the observations of one of the sharpest minds ever to pick up a pen, or shall we say, a quill.

If there’s one area where Austen’s real life and her fiction seem to nod knowingly at each other, it’s in the matter of love. We know she had her own brushes with romance. Some light-hearted, some serious, and some perhaps awkward.

Take Tom Lefroy for instance. He was the nephew of Jane’s close friends, and she met him in 1795. She wrote to Cassandra that she was “almost afraid to tell you how my Irish friend and I behaved.” The line drips with her usual irony. But the fact is they danced and flirted, and she admitted he was very agreeable. Yet, just like Elizabeth Bennett facing off with Mr. Darcy, social realities intervened. Lefroy’s family objected. Jane had no fortune and the romance was nipped in the bud. In fiction, Elizabeth wins the man against the odds. In life, Jane didn’t.

Then there’s Harris Bigg-Wither who proposed to Jane in 1802 and she accepted him and then by the next morning had changed her mind. Now that is a heroine’s move. It’s pure Emma Woodhouse in miniature. The confidence to say no to a man who was wealthy, practical, and would have secured her future simply because she couldn’t bear the thought of him. Her heroines often have that same courage. Elizabeth turning down Mr. Collins and Anne Elliot breaking off her engagement with Captain Wentworth. Acts of refusal that carried real risks just as Jane did.

But what fascinates me most is the irony. In her novels, the refusals are always rewarded with something better. The true love, the happy ending, the right man, after all. In Jane’s own life, the refusal left her with freedom, but also with uncertainty, dependence on her family, and the constant label of spinster. It’s tempting to see her heroines as imagined lives. But what might have been if the world had been kinder, or if her courage had been met with fortune rather than frustration?

So when Elizabeth Bennett teases Darcy or when Anne Elliot finally gets her second chance, I can’t help but feel Jane is letting her heroes live the endings she herself was denied.

If Austen’s romances hint at her personal longings, her family connections reveal some of her deepest frustrations. And nowhere is this more visible than in the story of her brother Edward Knight.

Edward was the lucky one. Adopted by wealthy cousins, he inherited great estates in Kent and Hampshire and lived the life of a landed gentleman. Meanwhile, after their father’s death in 1805, Jane, Cassandra, and their mother found themselves in far less secure positions. They relied on relatives, shifting from Bath to Southampton, never quite settled and certainly not comfortable or independent.

Now, Edward did eventually provide for them. In 1809, he offered them Chawton Cottage, the modest house near his Hampshire estate. This became Jane’s permanent home and the place where she produced her great novels. But it had taken four years to reach that point. Why? Partly, it seems, because Chawton wasn’t immediately available. Tenants had to move out before Edward could offer it. So, in fairness, it may not have simply been foot dragging.

Still, it’s difficult not to notice the irony. Edward was fabulously wealthy. His sisters and mother were not. He could have supported them more generously sooner, even if the cottage wasn’t vacant. By modern eyes, it looks like the help came late.

And here’s where life and fiction seem to echo each other. In Sense and Sensibility, the Dashwood women lose their home to an heir, John Dashwood, and his fashionable wife, Fanny. Promises of kindness dissolve into token gestures, and the Dashwoods are nudged into a smaller cottage dependent on family. Barton Cottage in the novel feels remarkably like Chawton Cottage in life. Second best but serviceable.

Of course, we can’t prove that Edward and his wife Elizabeth were Jane’s models for John and Fanny Dashwood, but the resemblance is striking. And one has to wonder: when Edward and Elizabeth read Sense and Sensibility, assuming they did in 1811, did they catch a glimpse of themselves on these pages? If so, Jane never admitted it. But knowing her, I like to think she enjoyed the irony.

So Chawton Cottage was both a symbol of dependence and the very foundation of Austen’s creative freedom. Just as her fictional Dashwoods make the best of Barton Cottage, Jane turned her second best house into the birthplace of literature that’s lasted for centuries.

If Austen’s family gave her stories their emotional backbone, the places she lived and visited gave them their settings. Again and again, we see her real surroundings reimagined in her fiction. Sometimes lovingly, sometimes with a good dose of satire.

Take Bath for example. When the Austen family moved there in 1801, it was considered the fashionable center of polite society, a place to see and be seen. But Jane never quite warmed to it. In her letters, she complains about crowded assemblies and tedious parties, and you get the sense she found the whole marriage market atmosphere a little wearing.

In Northanger Abbey, Bath becomes the backdrop for Catherine Morland’s wide-eyed adventures—excited at first, but also superficial, full of empty chatter and false friendships. And of course, in Persuasion, written years later, Bath is portrayed with even more sharpness. It’s where Anne Elliot feels most diminished, trapped in a city of appearances rather than substance. Bath, in other words, is Austen’s commentary on social performance born out of her own mixed experiences there.

Then there’s Lyme Regis. In 1804, Jane visited the seaside town, and her letters note the dramatic Cobb wall, the fine cliffs, and the dangers of slippery steps. These exact details resurface in Persuasion where Louisa Musgrove’s dramatic fall on the Cobb changes the course of the novel. It’s one of those moments where the line between travel diary and fiction almost disappears.

And we mustn’t forget the great houses. Through her brother Edward, Jane spent time at Godmersham in Kent, a proper estate with sweeping grounds and all the trappings of the landed gentry. You can feel echoes of it in the grandeur of Rosings Park in Pride and Prejudice or the comfortable elegance of Donwell Abbey in Emma. Jane knew firsthand what it meant to be a guest in such a house, enjoying their splendor while being keenly aware of the social divides that structured life within them.

What strikes me in all of these examples is how Austen transforms those places. Bath isn’t just a city, it’s a stage for vanity. Lyme isn’t just a seaside resort, it’s a site of passion and danger. And the great houses aren’t just pretty settings. They’re symbols of wealth, power, and social imbalance. She took what she saw and she sharpened it until each place became both real and metaphorical.

So whenever we walk through Bath in Northanger Abbey or along the Cobb in Persuasion or sit in the drawing room of Rosings, we’re actually walking with Jane Austen herself through places she knew, refracted through her fiction—at once familiar and transformed.

If you really want to glimpse the novelist behind the novels, you have to turn to Jane Austen’s letters. Not the ones Cassandra destroyed, sadly—hundreds were lost there—but the ones that survive. They give us Jane at her most unfiltered: witty, gossipy, sharp, and often merciless.

What’s striking is how much the tone of these letters feels like the DNA of her fiction. In 1796, for example, she described a neighbor as “being too tall and stout to be of any degree of elegance.” It’s a throwaway remark, but it has the exact same rhythm as one of her character sketches. You can almost hear Mrs. Elton or Sir Walter Elliot stepping off the page.

She was equally ruthless with fashion. In another letter, she mocked a young woman for looking “very plain” in a dress that failed to flatter her—the kind of commentary that resurfaces in every ball scene she ever wrote. And she could be savage about manners, too. One acquaintance had “manners which had not quite the air of the world.” That line could have walked straight into Emma.

Then there’s the travel writing. When Jane visited Lyme Regis, she described the Cobb wall and the dangers of slipping on stone steps. Years later, of course, Louisa Musgrove takes her infamous fall in Persuasion. You can almost trace the line directly from her letter to the finished scene.

What fascinates me is that these letters weren’t meant for the world. They were written to Cassandra or her nieces, never with publication in mind. Yet the wit, the irony, the sheer observational sharpness is all there. It’s as though her private correspondence was her sketchbook, the place where she honed her voice, tested her humor, and practiced the art of turning life into character.

Of course, it’s tempting to think of the letters as a kind of confession—Austen showing us the raw material of her novels. But perhaps it’s more accurate to say that both the letters and the novels come from the same place: her endless curiosity about people, her delight in irony, and the gift for seeing through pretension.

So when we read Lady Catherine De Bourgh pompously lecturing Elizabeth Bennett or Mrs. Elton bragging about her resources or even Sir Walter Elliot admiring his own reflection, we’re not just reading fiction. We’re hearing the same voice that Jane used in her letters: sharp, playful, and just a little bit cruel.

If there’s one question readers keep circling back to, it’s this: How much of Jane Austen herself do we find in her heroines? And the answer, I think, is both complicated and more revealing than it first appears.

Take Elinor Dashwood in Sense and Sensibility. She is the voice of restraint, patience, and endurance, quietly holding her family together while suffering disappointments of her own. There’s something of Jane in that steadiness, especially during those years of financial uncertainty after her father’s death when she and Cassandra had to rely on their brother’s charity.

Then there’s Elizabeth Bennett: witty, outspoken, unwilling to marry without affection. It’s hard not to see Jane Austen’s own sharp intelligence reflected in Elizabeth’s banter. And Elizabeth’s refusal of Mr. Collins mirrors Jane’s own refusal of Harris Bigg-Wither—the courage to say no even when society said yes.

Anne Elliot in Persuasion is more melancholy. She’s 27 at the beginning of the novel, considered “on the shelf,” haunted by the regret of having given up her first love. Here too we may hear echoes of Jane herself who, by that age, had also turned down a secure marriage and lived with the quiet awareness that her own chances were narrowing. Anne’s second chance with Captain Wentworth feels almost like a gift that Jane wished for but never received.

And then there’s Emma Woodhouse: the confident matchmaker, secure in her wealth and position. Emma may be the furthest from Jane’s lived reality, yet perhaps the closest to her imagination. Emma represents a life of independence, where a woman can meddle and scheme and make mistakes without her entire existence depending on her husband’s fortune. If Elizabeth is Jane’s wit and Anne is her regret, Emma may be her wish fulfillment—a heroine living with the freedoms Jane herself never had.

So, are these heroines autobiographical? Not exactly. They’re all facets of Jane Austen: her patience, her wit, her disappointments, her longings. In creating them, she wasn’t simply telling other people’s stories. She was refracting her own life into fiction, scattering herself across her novels in ways subtle and profound.

And that perhaps is why her heroines feel so alive to us still. Because through them, we’re not just reading about Elinor, Elizabeth, Anne, or Emma. We’re hearing the many voices of Jane Austen.

So, what have we seen? Jane Austen’s novels weren’t written in a vacuum. They resonate with the echoes of her own life: the romances she flirted with and refused, the frustrations of family dependence, the places she lived and disliked, and above all, the wit and irony that sparkle through her letters.

But Austen didn’t just copy her life onto the pages; she transformed it. Disappointments became comedy. Restrictions became satire. And her heroines became voices through which she could explore her own wishes, regrets, and even her imagined freedoms. Elizabeth’s defiance, Anne’s melancholy, Emma’s independence—all of them carry a fragment of Jane herself, refracted and reshaped until fiction and reality blurred together.

And maybe that’s why her novels endure. They aren’t simply love stories or comedies of manners. They are, in their way, Jane Austen’s attempt to portray the world she knew—sometimes faithfully, sometimes ironically, and maybe sometimes as she wished it could be.

Now, before I close, I want to bring in a brilliant suggestion I received from J Dylan 3035, and I’ll pop it on the screen for you now. She said:

“For a fun twist on your videos, could you do an episode where you ask your female audience which of Austen’s characters they most relate to and maybe who they’d choose as a best friend? For your male listeners, which of Austen’s heroines would you be most attracted to?”

I think it’s a wonderful idea, and I’d love to hear your thoughts. So obviously comment below, right? Which of Austen’s characters do you see yourself in? Who would be your closest companion? Or maybe right across the board, including her male characters? And if you’re feeling bold, who would you fall for?

Because at the heart of it, Austen’s novels are about connection—about seeing ourselves, our friends, even our family in the characters she created. And if Jane Austen could weave her own life into her fiction, then surely we can weave a little of ourselves into our reading of her. It’s worth thinking about, I’m sure.

I’ll wrap this one up for now.