鲁迅英文纪录片:一位文学巨匠的觉醒与抗争之路

今天,我们将探索一位作家的故事。如果我将焦点集中在19世纪,能说出多少位伟大的作家?法国的维克多·雨果、英国的查尔斯·狄更斯、印度的罗宾德拉纳特·泰戈尔、德国的弗里德里希·席勒、俄国的列夫·托尔斯泰、美国的马克·吐温和艾米莉·狄金森。那么,中国呢?考虑到其文学成就及对后世的影响,我想大多数中国人都会给出同一个名字——鲁迅。

今天的故事,从一个老式的四合院开始。

一、沉寂的公务员岁月

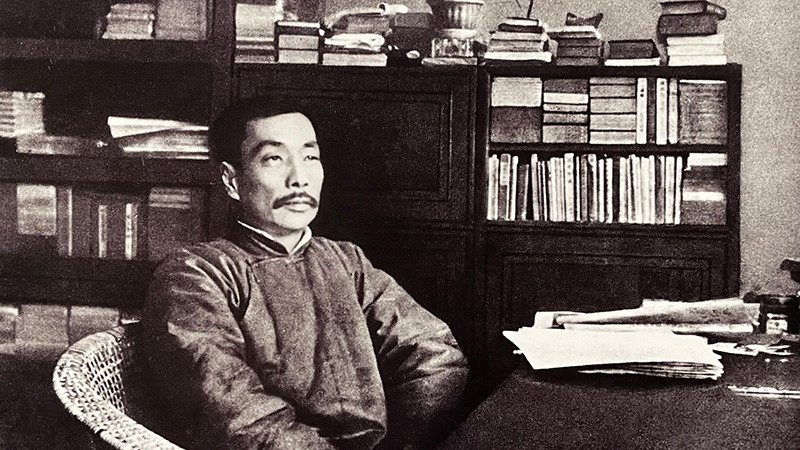

这是1917年的夏天,鲁迅36岁。他已在这间昏暗的屋里居住了大约六年。这是一张鲁迅与教育部同事的合影,他看上去相当普通。很长一段时间里,鲁迅在北京国民政府教育部做着一份朝九晚五的公务员工作。他这样描述自己:“见过辛亥革命,见过二次革命,见过袁世凯称帝,见过张勋复辟,看来看去,就看得怀疑起来,于是失望,颓唐得很了。” 然而他写道:“但我却又怀疑于自己的失望……因为这于我太痛苦。我于是用了种种法,来麻醉自己的灵魂,使我沉入于国民中,使我回到古代去,后来也亲历或旁观过几样更寂寞更悲哀的事,都为我所不愿追怀,甘心使他们和我的脑一同消灭在泥土里的。”

这是钱玄同,鲁迅在日本留学时的同窗,一位古文字学专家。自1917年8月起,钱玄同频繁拜访鲁迅。他们之间有一段著名的对话:“假如一间铁屋子,是绝无窗户而万难破毁的,里面有许多熟睡的人们,不久都要闷死了,然而是从昏睡入死灭,并不感到就死的悲哀。现在你大嚷起来,惊起了较为清醒的几个人,使这不幸的少数者来受无可挽救的临终的苦楚,你倒以为对得起他们么?” 鲁迅答道:“然而几个人既然起来,你不能说决没有毁坏这铁屋的希望。”

二、新文化的曙光

这是来自绍兴的蔡元培。1916年,他出任北京大学校长。这是陈独秀,1916年9月1日,他主编的《新青年》杂志发表了《敬告青年》一文。这是胡适,他于1917年6月从哥伦比亚大学回国,成为北大最年轻的教授。这是李大钊,1917年底,他出任北京大学图书馆主任。

蔡元培邀请创办《新青年》的陈独秀来北大任职,吸引了许多新知识分子。《新青年》杂志与北京大学的文科学部,悄然推动着即将席卷中国的新文化运动。

1918年5月,鲁迅的短篇小说《狂人日记》在《新青年》上发表。他借一个“狂人”之口,愤怒地抨击了那套盛行了两千年的“吃人”的旧道德:“我翻开历史一查,这历史没有年代,歪歪斜斜的每叶上都写着‘仁义道德’几个字。我横竖睡不着,仔细看了半夜,才从字缝里看出字来,满本都写着两个字是‘吃人’!”《狂人日记》的主题直指传统礼教如何摧残人性,以其独特的方式在当时具有开创性意义。鲁迅由此加入了五四运动的行列——一场于1919年兴起的反帝爱国的文化政治运动。

(专家评论:)他利用“狂人”这样一个特殊的人物——狂人就是疯子,是一个病人。他以这个人物的突然疯狂,同时又突然清醒,用他的疯狂摆脱了我们习以为常的日常世界,借此来表达他思想的突然清醒。他把中国传统社会、传统文化里的问题,突然就认识到了。鲁迅从这里头生发出这样一个预言性的小说,实际上才代表了鲁迅在新文化运动中的地位,一下子振聋发聩。读者看到了以后,有一种惊悚的感觉。《狂人日记》被称为中国现代文学的开山之作。我认为它之所以具有预言性,是因为鲁迅借此要表达的,是一个大时代的重大议题。

三、故乡与童年:甜蜜与苦痛的根源

一百多年前,鲁迅出生在中国东南部一个河道纵横交错的小城——绍兴。那是1881年,中国最后一个封建王朝灭亡的三十年前。“我于一八八一年生于浙江省绍兴府城里的一家姓周的家里。”鲁迅在自传的开篇如此写道。1881年9月25日(清光绪七年八月初三),周家为迎来了家族的长孙而兴奋不已。婴儿被命名为周樟寿,小名阿张。

鲁迅对故乡绍兴的感情是复杂的。在许多作品中,他对这座城市的记忆流露出热爱、敬意与温暖的怀念;而在另一些作品中,则传递出憎恶、排斥与敌意。这与他早年经历的艰辛和人世冷暖密切相关。绍兴是城市文化与乡村文化的混合体。鲁迅自幼接受了良好的儒家经典教育与日常生活习俗的熏陶,二者都深深扎根于中国传统文化。在鲁迅生命的最后五十年里,故乡的风景、习俗、戏曲与文化,成为他生命中仅存的诗意记忆,时常抚慰着他的心灵。

1893年,灾难降临到这个古老的大家庭。鲁迅的祖父周福清因替亲戚科场行贿事发而入狱。尽管他主动投案,但那一年,13岁的鲁迅为躲避可能牵连的惩罚,不得不与弟弟周作人逃往乡下,过着寄人篱下的生活。祸不单行,祖父入狱的第二年,他的父亲突然重病。对鲁迅而言,故乡的宁静生活就此永远结束了。作为家中长子,鲁迅承受着持续的情感压力。在他的记忆里,这是一道无法愈合的创伤。

由于父亲病重,鲁迅无法专注于在“三味书屋”学习那些被视为教育关键的古代经典。相反,他几乎每天奔波于当铺和药铺之间,寻找稀有的中药材。他后来回忆,自己如何在当铺里遭受冷眼,又如何屡屡被庸医愚弄。后来,在作品《父亲的病》中,他描述了这段为父亲典当抓药的痛苦经历。父亲的病与死,如同巨大的阴影笼罩着整个家庭。随着父亲的离世,家道急剧中落。从一个大家庭的少爷,到寄人篱下的“乞食者”,鲁迅过早地进入了社会。多年后他回忆,仍能感受到一颗年轻心灵的愤懑。他慨叹:“有谁从小康人家而坠入困顿的么,我以为在这途路中,大概可以看见世人的真面目。” 青年鲁迅经历的这两大家庭变故,对其心理健康造成了严重损害,留下了终生难以愈合的情感创伤。多年的避难与求医经历,也使鲁迅对社会人生与人情世故有了清醒的认识。

(专家评论:)鲁迅对故乡,对故乡里的人是最为熟悉的。而且这个江南绍兴故乡,也是最典型的古老中国社会的缩影。早期记忆对鲁迅来说非常重要,而且他一生一直没有摆脱早期的记忆。他去世之前写的几篇文章,都是跟故乡有关的,看来是刻骨铭心的。这对他创作也好,对他思想的形成都起了很大的作用。

四、出走与求索

1898年,17岁的鲁迅走到了人生的十字路口。父亲去世后,他在故乡成了一个“边缘人”。尽管家贫难以度日,母亲仍希望他继续学业,走科举正途。然而,经历家庭变故的他,对科举之路充满了憎恶与恐惧。但出路何在?鲁迅在一篇文章中描述了自己的心境:“S城人的脸早经看熟,如此而已,连心肝也似乎有些了然。总得寻别一类人们去,去寻为S城人所诟病的人们,无论其为畜生或魔鬼。”年轻的鲁迅决心离开家乡。

1898年5月,鲁迅怀着沉重的心情,带上母亲筹措的八元川资,登上了一艘小船。他后来回忆:“走异路,逃异地,去寻求别样的人们。”这是江南水师学堂的旧址。在南京求学的近四年间(1898-1902),中国正处于前所未有的动荡之中:甲午战败,经历了戊戌变法的血雨腥风;1899年,义和团运动风起云涌;1900年,八国联军入侵北京,外国军队将意志强加于中国。从青少年到成年早期,鲁迅经历的是一个积贫积弱、处于历史最低点之一的中国。连绵的战火将整个国家推向崩溃的边缘。

也正在此时,21岁的鲁迅踏上了赴日留学之路,这是他人生的一大转折点。1902年,鲁迅以第三名的成绩从江南陆师学堂附设矿路学堂毕业。此时,清政府正资送学生留日,鲁迅被选中。目睹日本明治维新后的迅速发展,清政府认为向日本学习是学习西方的捷径。1896年,清政府派遣了13名学生赴日留学。到1902年鲁迅抵达时,已有不少中国学生在日,留学日本蔚然成风。

鲁迅发现,国力日渐强盛的日本,其称霸东亚的野心也在膨胀。几年前日本击败了中国的北洋海军,整个日本社会弥漫着对华人的轻蔑。来自日本人的鄙视与同胞们不争气的行为,开始改变鲁迅的思想。他最初立志学医,并写道:“我的梦很美满,预备卒业回来,救治像我父亲似的被误的病人的疾苦,战争时候便去当军医,一面又促进了国人对于维新的信仰。”然而,一次偶然看到的幻灯片改变了他的想法。

1905年日俄战争爆发,日俄两国在中国领土上厮杀,争夺在华势力范围,中国政府竟宣布中立。鲁迅密切关注战事进展。一次课间,鲁迅看到一段关于战争的幻灯片,其中一群中国人正在围观一个被当作俄国间谍处决的同胞。他深受震撼。正如他后来回忆,这段幻灯片使他决定弃医从文。鲁迅开始学习德语和俄语,翻译欧洲弱小民族的文学。在其著作中有一句广为流传的话:“凡是愚弱的国民,即使体格如何健全,如何茁壮,也只能做毫无意义的示众的材料和看客,病死多少是不必以为不幸的。所以我们的第一要著,是在改变他们的精神。”

(专家评论:)鲁迅在日本留学的时候,他是通过日本这个桥梁,瞭望到了世界。他对整个人类发展的历史,有了一种切身的体会。他到了日本留学之后,中国人的身份,就像他早年时候那种经验一样,带给他的屈辱感、挫败感,就成为了一种深刻的体验。

五、无爱的婚姻与漫长的牺牲

鲁迅在日本求学期间意气风发,积极追求新思想,却接到了母亲催他回国完婚的信。他回信说:“觉得朱安姑娘和我似不合适,请母亲回掉。”母亲则发电报称:“母病速归。”一场婚礼正在故乡绍兴等待着他。那是1906年,鲁迅26岁。在亲戚眼中,他是个不守规矩的年轻人:放弃科举正途、剪掉辫子、学洋文、穿洋装。他们担心他会破坏婚礼的传统礼仪,但一切顺利进行,连他母亲都感到意外。新娘来自绍兴一个普通家庭,人们称她为“安姑”,她比鲁迅大三岁。

(回忆述说:)成亲的时候,花轿抬来,因为朱安裹脚,脚小绣花鞋大,还没下轿呢,绣花鞋就掉下来了,这是一个非常不好的象征。到了拜堂的时候,鲁迅也是被迫拜堂。但后来一看见新娘原来是这个样子,就非常难过。

在这场喜庆的婚礼上,无人知晓这竟是一场漫长悲剧婚姻的开始。鲁迅陷入绝望,这影响了他的思想和未来梦想。他的妻子朱安承受着比鲁迅更深的痛苦。鲁迅后来说:“这是母亲给我的一件礼物,我只能好好地供养它,爱情是我所不知道的……我之所以甘愿背负古老的鬼魂,乃至牺牲自己,是因为我对四千年来的历史并无亏欠。”四千年太久,而人生只有短暂的数十年。

(专家评论:)鲁迅跟朱安的婚姻呢,后来他自己说的是:最苦的不是敌人射来的毒箭,而是自己亲人误给的毒药。他又爱他的母亲,不愿意伤母亲的心,但是对朱安呢,他又无法接受。所以后来他跟许广平说:这不是我的媳妇,是母亲送给我的一个礼物,我只好养着她,爱情是谈不上的。

婚礼后的第四天,鲁迅便与弟弟周作人及几位朋友启程重返日本,一去三年。数年的留日学习后,鲁迅于1909年离开东京回国。这是鲁迅回国不久的照片,西装领带,显得精神抖擞。然而,辛亥革命后的两年,他在绍兴师范学校露面时,却是另一番模样。直到写下《狂人日记》、加入《新青年》、遇到一群志同道合的伙伴,鲁迅才终于抵达了人生的突破点。

“一艘乌篷船在暮色中缓缓前行。深冬,湿冷,寒风扫过游子悲凉沉郁的心头。”一年后,在小说《故乡》中,鲁迅吐露了自己的心绪:“老屋离我愈远了;故乡的山水也都渐渐远离了我,但我却并不感到怎样的留恋……我只觉得我四面有看不见的高墙,将我隔成孤身,使我非常气闷。” “希望是本无所谓有,无所谓无的。这正如地上的路;其实地上本没有路,走的人多了,也便成了路。”

六、文坛巨擘的崛起与担当

离开故乡后,鲁迅前往北京,先后在七所大学任教。他发表的作品赢得了巨大的认可,创作涵盖小说、散文诗、杂文,且不仅用文言,更用白话写作,使其作品能为大众所接受。1919年,鲁迅在北京旧城区买下一处四合院。鲁迅在八道湾胡同11号频繁会客,来访者多为知名学者。周氏兄弟很好客。一日,周作人邀请蔡元培来访,蔡元培向兄弟俩发出了到北京大学任教的邀请。自1920年起,鲁迅受聘于北京大学、北京高等师范学校等北京七所院校任教。他的《中国小说史略》研究在学术界广受欢迎。在文学界,他的影响力有目共睹,被尊为沈雁冰在郑州创办的文学研究会的重要指导者,也是浅草社、未名社、沉钟社等文学社团的导师,被视为文坛领袖。他还与友人创办了《语丝》周刊、未名社和莽原社。同时,鲁迅热衷于艺术创作,相继发表《狂人日记》、《阿Q正传》等小说,引起了北京、上海等地读者的极大关注。《狂人日记》甚至被选入小学课本。

20世纪前二十年,中国社会动荡不安。鲁迅在1920年代的小说,如手术刀般剖开了中国社会严峻的现实。

(有人说:)《阿Q正传》同时也代表了人类的普遍特点,所以这的确是一个在世界史上具有重要意义的文学典型。他一生创作了三百万字的作品,你发现都是前无古人的,都是新的。他没有被旧的文化所束缚,完全是一种新诞生的文化种类、文学种类。

中篇小说《阿Q正传》是他最著名的作品,也是中国现代文学史上被评论最多的小说,已被译成多种语言。阿Q的形象在他心中酝酿多年。鲁迅曾说,他从事文学的目的是为了唤醒沉睡的民众。

(原文引用:)我要给阿Q立传……传的名目很繁多……最后,便从不入三教九流的小说家所谓‘闲话休提,言归正传’这一句套话里,取出‘正传’两个字来,作为名目。

(专家评论:)《阿Q正传》它是一种隐喻。在这里边,通过一个人物形象,它折射出很丰富的我们民族生活的图景。我觉得这一点,鲁迅为我们文学史,不仅为中国文学史,也为世界文学史贡献了一个奇特的典型形象。

七、家庭变故与情感重生

1923年夏天,八道湾四合院的气氛突然紧张起来,家庭突发变故,兄弟二人反目。事情发生得非常快。7月14日,鲁迅在日记中写道:“是夜始改在自室吃饭,自具一看,此可记也。”

(专家评论:)家庭的变化对鲁迅的影响还是很大的,特别是他和他二弟周作人之间的矛盾。后来他们分道扬镳,这对鲁迅刺激很大。他当时喝酒喝了很多,就感觉到非常的痛心,弟弟就这样和自己……这种友情就没有了,兄弟之情就结束了。这对鲁迅伤害很大。作为长子来讲,他就像父亲一样掌管着这个家,有很高的责任感。因此这种责任感也放大到社会上,在社会上他也是时刻想着中国,想着中国的革命,中国人的解放。这应该是纠缠着鲁迅一生的一个观念。兄弟失和是对他的一个极大的打击,也是把他的文学作品推向极致、成熟的一个标志。但是在这之后,鲁迅又和许广平恋爱,又走出了这个极度失望和绝望的深渊,恢复了他原来的状态。这实际上是一场爱情把他给拯救了。

1925年,45岁的鲁迅坠入爱河。他心仪的对象是他的学生之一,年龄比他小近二十岁。起初,他们通信讨论人生与社会,爱情便在这些信件中滋长。他们的爱情故事始于书信往来。一个月后,许广平首次拜访鲁迅,她称之为一次“探险”。在她眼中,鲁迅那间名为“老虎尾巴”的书房充满了奇异的色彩:“坐在那间一面满镶玻璃的室中时,是时而听雨声的淅沥,时而窥月光的清幽……当枣树发叶结实的时候,则领略它微风振枝,熟果坠地……”这次拜访后,他们的信件似乎开始流露出浪漫的情愫。他们不仅谈论社会与人生,也互相打趣调侃。此后,许广平拜访鲁迅更加频繁。

这是一封情书,更是一部情书集。鲁迅是中国历史上第一位出版自己情书的作家。这些书信里虽有昵称和私语,但更多的是鲁迅与他的学生之间关于中国过去、现在与未来的对话。似乎这位年轻女性的爱,给了鲁迅从黑暗深渊中振作起来的巨大力量。许广平所写的这首热情洋溢的散文诗,更像是一篇爱情宣言:“它也许会出轨,也许不合规矩……这些于我们不相干,于你们无关系。”

1927年10月3日,鲁迅与许广平抵达上海。五天后,他们搬入虹口区景云里23号。随着南方革命的进展,一场旨在建立统一国家的运动展开,中国的文化中心逐渐从古都北京转移到具有浓厚国际色彩的上海。上海像一个喧闹的大舞台,这里既是激进革命作家的诞生地,也是旧派文人的大本营。在变幻的时局中,上海开始展露其耀眼的光芒。鲁迅生命中最后的十年,便是在这样的环境中度过。

八、上海十年:战斗、友情与温情

在孤独的黑暗中,鲁迅喜欢与几位年轻朋友谈论社会、人生与文学。从清晨到午后,他不知不觉扮演着父亲般的角色。在这些照片中,我们看到鲁迅与柔石、冯雪峰等友人活泼而温馨的场景。这些年轻人常陪伴在鲁迅身边,看电影、游泳或参观艺术展览。然而,他们的友情常常被政治的残酷所笼罩。几年后,年轻的左翼作家柔石在鲁迅面前被枪杀。他在诗中悲叹:“忍看朋辈成新鬼,怒向刀丛觅小诗。”他也目睹了中国民权保障同盟总干事杨铨的被害,痛惜“何期泪洒江南雨,又为斯民哭健儿。”

(专家评论:)他很有责任感。萧红萧军到上海的时候没有钱,他们跟鲁迅借钱,第一次见面鲁迅就给他们一笔钱,让他们能够暂时在上海安顿下来。就是这种责任感,这种父爱般的责任感,不仅在家庭里面,在他在左联时期,对待青年艺术家和文学家都表现得淋漓尽致,很让人感动。他是很有爱意、很有暖意的一个人,有责任感的人。

1929年9月26日,许广平在医院即将生产。鲁迅在她的床头轻轻放了一小盆松树盆景,日夜陪伴,几乎不曾离开。鲁迅为即将成为父亲而兴奋。第二天许广平出院回家,发现家里又多了一盆精巧的松树盆景。更令她惊讶的是,鲁迅按照护士的要求重新布置了家具,打扫了每个角落,而他平时很少关注这些琐事。孩子在上海出生,鲁迅为他取名“海婴”,意为“上海出生的婴儿”。他说这名字只是暂用,孩子长大后可以改。医生建议请个保姆,但鲁迅坚持要亲自照顾孩子。由于夫妇俩没有育儿经验,他们事事谨慎,严格按照育儿指南操作,从哺乳到洗澡。尽管如此,婴儿还是常感饥饿或着凉,他们不得不请教医生并最终请了保姆。

在周海婴的记忆中,家中典型的一天是这样开始的:“父亲往往得陪客人聊一下午……谈话通常持续很长时间。我能听到笑声,有时也会加入他们。我不知道客人们夜里何时离开,因为我已经睡着了。”夜深海婴入睡后,鲁迅在灯下写作,许广平则在一旁读报或做手工。与许广平在上海的岁月,是他除童年外一生中最好的时光。他曾对许广平说:“我要为中国做点事,才能对得起你。”相识十年后的1934年12月,鲁迅为许广平题诗一首:“十年携手共艰危,以沫相濡亦可哀。聊借画图怡倦眼,此中甘苦两心知。”

(专家评论:)所以在中国社会最黑暗最无望的时候,鲁迅先生的文字里面,你会感觉到他虽然接受了那么多的黑暗,写了形形色色的丑陋的人物,他和现象界里面那些魑魅魍魉的搏斗所表现出的毅然决然的精神,并没有让你感觉到他阴冷,而且感觉到他身上是有一种热流在里边。所以这个就是一种担当感。鲁迅先生他不仅承担了家庭的义务,他也肩负起了社会的这个责任。鲁迅作为一个现代知识分子,体现了他的责任,体现了他的使命感,体现了他的情怀。这个呢,又是有非常值得宝贵、非常值得我们学习继承的东西。他对于社会、对于民族、对于国家、对于文化、对于学术、对于文学,都有极强的那种使命感跟责任感。鲁迅的一生就是反抗绝望,反抗奴性,希望人从奴性的人成长为自觉的人,这是他最深的一个价值。鲁迅能够把他一个具体的家族的经验,和这个中华民族的民族国家在现代世界里面所遭受的那种遭遇,把这个东西合到一起来表达。所以在鲁迅的创作里边,个人的经验、家族的经验,都不是仅仅属于个人和这个家庭的,他同时呢,也是属于我们中华民族的,也是属于我们国家的一种集体的经验。在这个民族走向绝望、没有路可走的时候,他用自己的智慧,和自己生命的这种热能,他抵抗黑暗而肉搏这个惨淡的暗夜。他用生命自身的燃烧,发出光热来照亮了周围的世界,使我们感到我们这个世界还没有完全的沦丧。所以他感召了很多青年人走上了思想解放和文化解放的道路。

九、最后的日子与不朽的丰碑

1936年,鲁迅疲惫而苍老。虽然他只有56岁,但健康状况在1928年一场大病后每况愈下。他一直遭受肺结核和胸膜炎的折磨,经常发烧咳嗽。起初症状尚可用药物控制,但最终药物开始失效。1934年秋,他持续发烧一个月,变得更加消瘦,颧骨高耸,牙龈变形,无法佩戴假牙,不得不请医生修正。大部分时间里,鲁迅沉默地坐在躺椅上,闭目养神,手中香烟的烟雾缓缓升起。

在生命的最后十年里,鲁迅用写作拥抱了一个知识分子对社会的责任,为后世留下了不朽的文学丰碑。他用工作麻醉自己、安慰自己、鼓励自己;他与死亡抗争;他用工作来回应关心他的朋友,回击他的敌人。“赶快做”是他晚年的人生信条之一。

1936年10月18日凌晨,鲁迅哮喘突然发作。历经56年的艰辛跋涉,他终于走到了生命的终点。鲁迅逝世的消息迅速传开,震动了整个上海。他的儿子海婴当时年仅七岁。几位年轻艺术家如曹白、力群为鲁迅画了最后的素描。他看起来消瘦而疲惫。一位日本牙医为鲁迅制作了石膏遗容面膜,保留了他的胡须与眉宇。欧阳予倩和明星影片公司的一个团队为他的葬礼拍摄了纪录片。他的遗体上方悬挂着蔡元培撰写的挽联:“著述最谨严非徒中国小说史,遗言太沉痛莫作空头文学家。” 一支由七千人组成的送葬队伍,在宋庆龄等人的带领下,护送他的灵柩前往万国公墓。队伍前方高举着司徒乔为他绘制的肖像。一路上,人们高唱特地为纪念他而谱写的挽歌:“你的笔尖是枪尖,刺透了旧中国的脸;你的声音是晨钟,唤醒了奴隶们的迷梦。”

The Story of Lu Xun: The Awakening and Struggle of a Literary Giant

Today we are going to explore the story of a writer. If I narrow the focus to the 19th century, how many great writers can I name? Victor Hugo of France, Charles Dickens of Great Britain, Rabindranath Tagore of India, Friedrich Schiller of Germany, Leo Tolstoy of Russia, Mark Twain and Emily Dickinson of the United States. But what about China? Considering his literary achievements and his influence on later generations, I think most Chinese would offer the same name: Lu Xun. The story today starts with an old courtyard-style house.

I. The Silent Years of a Civil Servant

This is the summer of 1917. Lu Xun was 36 years old. He had lived in his dark room for about six years. This is a photo of Lu Xun and his colleagues at the Ministry of Education. He looks quite ordinary. For a long time in Beijing, Lu Xun worked as a nine-to-five civil servant in the Ministry of Education for the Nationalist government. He described himself as having seen the 1911 Revolution, the Second Revolution, Yuan Shikai’s proclamation to the throne, and the Manchu Restoration. “The more I see, the more skeptical, disappointed and downhearted I get,” said Lu Xun. “But I have to expel my own loneliness because it’s killing me. I tried many ways to numb my soul. I submerged myself into the public and tried to return to ancient times. Later I experienced a few more tragic events which I don’t want to recall. I wish to bury them in the soil together with my brain.”

This is Qian Xuantong, Lu Xun’s schoolmate in Japan, an expert in paleography. Since August 1917, Qian Xuantong paid frequent visits to Lu Xun. They had a famous conversation: “Imagine many people were sleeping in a windowless iron house that is extremely difficult to escape, and they will soon die painlessly in their sleep from suffocation. Do you think you are doing them a favor by waking them up to face the agony and dying helplessly?” Lu Xun replied, “Since some people are up, you can’t say there is not a minor chance of the breakout of the iron house.”

II. The Dawn of the New Culture Movement

This is Cai Yuanpei from the city of Shaoxing. In 1916, he became president of Peking University (the former Imperial University of Peking). This is Chen Duxiu. On September 1st, 1916, his article “Call to Youth” was released in the inaugural issue of New Youth magazine. This is Hu Shi. He returned to China from Columbia University in June 1917 and was the youngest professor at Peking University. This is Li Dazhao. At the end of 1917, he became head of the Peking University library.

Cai Yuanpei invited Chen Duxiu, who founded New Youth magazine, to Peking University, which attracted many new intellectuals. New Youth magazine and Peking University’s College of Liberal Arts quietly created what became China’s New Culture Movement.

In May 1918, Lu Xun’s short story “A Madman’s Diary” was released in New Youth magazine. Through the words of a “madman,” he angrily attacked what he called the old “man-eating” moral codes which had prevailed for two thousand years. “I remember, though not very clearly, that in ancient times, people were often eaten. I looked in a history book with no records of what age it was. Phrases of virtue and morality are written carelessly everywhere on the pages. I cannot fall asleep at night, so I looked more carefully and saw one word everywhere between the lines: ‘Eat people.'” The theme of “A Madman’s Diary” is how traditional moral codes are destroying humanity. This was groundbreaking at the time in such a unique way. Lu Xun joined the ranks of the May Fourth Movement, an anti-imperialist, cultural and political movement which emerged in 1919.

(Expert Commentary:) 他利用“狂人”这样一个特殊的人物——狂人就是疯子,是一个病人。他以这个人物的突然疯狂,同时又突然清醒,用他的疯狂摆脱了我们习以为常的日常世界,借此来表达他思想的突然清醒。他把中国传统社会、传统文化里的问题,突然就认识到了。鲁迅从这里头生发出这样一个预言性的小说,实际上才代表了鲁迅在新文化运动中的地位,一下子振聋发聩。读者看到了以后,有一种惊悚的感觉。《狂人日记》被称为中国现代文学的开山之作。我认为它之所以具有预言性,是因为鲁迅借此要表达的,是一个大时代的重大议题。

III. Hometown and Childhood: The Source of Sweetness and Pain

More than 100 years ago, Lu Xun was born in Shaoxing, a town crisscrossed by canals and waterways in southeastern China. The year was 1881, thirty years before the demise of China’s last feudal dynasty. “I was born in 1881 into the Zhou family in Shaoxing city, Zhejiang province,” wrote Lu Xun at the very beginning of his autobiography. It was September 25, 1881. The Zhou family was excited to have the first grandson of the family. The baby was named Zhou Zhangshou and affectionately called A Zhang.

Lu Xun had mixed feelings for his hometown of Shaoxing. In many of his works, he showed love, reverence, and warm reminiscence of the city; while in others, he conveyed hatred, rejection and malice towards it. This is closely related to his early experiences of hardship and the fickleness of human nature. Shaoxing was a mixture of both city culture and village culture. Since childhood, Lu Xun received a good education in both Confucian classics and customs of everyday life, both closely connected to traditional Chinese culture. In the last fifty years of Lu Xun’s life, the landscapes, customs, traditional opera and culture in his hometown were the only poetic memories he had. These sweet memories often comforted his heart.

In 1893, a disaster fell upon this large old family. Lu Xun’s grandfather, Zhou Fuqing, was imprisoned for bribing an imperial examiner for a relative. Despite his voluntary surrender to the court, that year Lu Xun was thirteen years old. To avoid collective punishment, Lu Xun and his younger brother Zhou Zuoren lived in the countryside, living in exile. Misfortunes never come alone. The next year after his grandfather was imprisoned, his father suddenly fell seriously ill. For Lu Xun, the peaceful life in his hometown ended forever. As the eldest son of the family, Lu Xun was under constant emotional stress. In his memory, this was an incurable trauma.

Due to his father’s illness, Lu Xun couldn’t focus on learning ancient classics during what is called the “Three Flavor Study,” a key part of traditional education. Instead, he visited pawnshops and pharmacies almost every day, looking for rare Chinese medicinal herbs. He recalled later how he was scorned bitterly in the pawnshops and repeatedly teased and fooled by physicians. Later, in his work “Father’s Illness,” he described his painful experience of visiting pawnshops and looking for medicine for his father. The illness and death of his father shrouded the entire family like a huge shadow. Following the loss of his father, the family’s financial status declined sharply. From a child of a large family to a beggar living under others’ roof, Lu Xun entered into society prematurely. After many years, he recalled he could still feel the indignation of a young heart. He lamented, “I wonder if there is anyone else who has fallen from a well-off family into a dead corner. I think you will probably see the real world along the way.” The two major domestic misfortunes young Lu Xun experienced caused serious damage to his mental health, leaving deep, open emotional wounds for a lifetime. Living as a refugee and seeking medicine for so many years, Lu Xun had gained a sober understanding of social life and the true colors of human nature.

(Expert Commentary:) 鲁迅对故乡啊,对故乡里的人是最为熟悉的。而且这个江南绍兴故乡,也是最典型的啊中国古老社会的那一个缩影。早期记忆对鲁迅来说非常重要,而且他一生他这个一直没有摆脱早期的记忆。他去世之前写的有几篇文章,都是跟故乡有关的,看来就是刻骨铭心的。这是对他创作也好,对他思想的形成都起了很大的作用。

IV. Leaving Home and Seeking a Path

In 1898, Lu Xun was 17 years old. He arrived at a crossroads in his life. After losing his father, he became a marginal man in his hometown. Although the family was very poor and could barely make ends meet, he was asked by his mother to carry on with his studies and take the imperial examination. However, with the two incidents hanging over him, he hated and feared the “right way” of imperial examinations. But where to go? Lu Xun described his state of mind in an article: “I am familiar with every face and even every soul in the S city. I have to find a different kind of people, those despised by the people here, even if they are beasts or devils.” The young Lu Xun was determined to leave home.

In May 1898, Lu Xun boarded a small boat with a heavy heart and eight yuan he borrowed from his mother for traveling expenses. He later recalled, “I walked on a different path, to a different place, to look for different people.” This is a former site of the Jiangnan Naval Academy. During the nearly four years Lu Xun studied in Nanjing, China was in unprecedented turmoil: after losing the Sino-Japanese War, it went through the violence and madness of the Reform Movement of 1898; in 1899 the so-called Boxer Rebellion raged like a storm; in 1900, Beijing was invaded by the Eight-Nation Alliance forces, foreign troops who imposed their will on China. Throughout his teenage years and into early adulthood, Lu Xun experienced a China that was poor and weak, a nation at one of the lowest points in its history. Near-continuous war brought the entire country to the verge of collapse.

It was at this time that the 21-year-old Lu Xun went to study in Japan. This was a major turning point in his life. In 1902, Lu Xun graduated with high scores from the School of Mines attached to the Jiangnan Army Academy. At this time, the government was sponsoring students to study in Japan, and Lu Xun was chosen to be one of them. Having witnessed the rapid development of Japan after the Meiji Restoration, the government believed that learning from Japan was a shortcut to learning from the West. In 1896, the Qing government sent thirteen students to study in Japan. By 1902 when Lu Xun arrived in Japan, there had already been a number of Chinese students there; studying in Japan became very popular.

Lu Xun discovered Japan, whose national strength was growing, as was its ambition to dominate East Asia. Japan had beaten China’s Beiyang Navy a few years earlier, and the whole nation was suffused with a disdain for the Chinese. Contempt from the Japanese and the indecent actions of his countrymen began to change Lu Xun’s thoughts. He began to consider becoming an author instead of a physician. He wrote, “My dream is very beautiful. After graduation, I will treat patients properly, not in the way physicians treated my father. During wartime, I could join a combat medical team while promoting people’s faith through reforms.” He changed his mind by chance after he saw these photos.

The Russo-Japanese War broke out in 1905. Japan and Russia were fighting on Chinese territories, vying for spheres of influence in China; the Chinese government declared its neutrality. Lu Xun paid close attention to the progress of the war. During a break, Lu Xun saw a few slides about the war in which a group of Chinese were watching a fellow countryman being executed. He was deeply shocked. As he later recalled, this slideshow made him decide to become an author instead of a physician. Lu Xun began to learn German and Russian and translate the literature of weak European nationalities. This is a well-known quote from his work: “The weak citizens, however strong they are physically, are only meaningless display models and onlookers. Their diseases or death are not necessarily considered unfortunate. So our top priority is to change their spirit.”

(Expert Commentary:) 鲁迅在日本留学的时候,他是通过日本这个桥梁,他瞭望到了世界。他对整个人类发展的历史,他有了一种切身的体会。他到了日本留学之后,这个中国人的身份,就是像他早年的时候那种经验一样,带给他的屈辱感,带给他的挫败感,然后呢就成为了一种深刻的体验。

V. A Loveless Marriage and a Long Sacrifice

Lu Xun was high-spirited and vigorous in his pursuit of new ideas in Japan. Then he received a letter from his mother urging him to return and get married. He replied, “I think it is better for my proposed bride to marry another man.” His mother telegraphed: “Your mother is sick. Come back soon.” A wedding was waiting for him at his hometown of Shaoxing. It was 1906. Lu Xun was 26. In the eyes of his relatives, he was an unruly young man who abandoned the right path of the imperial examination: he cut the braid typical of Chinese men, learned foreign languages, and wore foreign clothes. They worried he would sabotage the traditional etiquette of the occasion, but everything went on smoothly, even his mother was surprised. The bride was from an ordinary family in Shaoxing; people called her An. She was three years older than Lu Xun.

(Recollection:) 据这个回忆说,成亲的时候,这花轿抬来,因为那个朱安的那个裹脚,脚小啊那绣花鞋大,还没下那个轿呢,绣花鞋就掀掉了,这是一个非常不好的象征。就到那个去拜堂啊什么的,鲁迅也是被迫的去拜堂。但后来一看见这个新娘原来是这个样子,就非常难过。

At the cheerful wedding, people had no idea that this was the beginning of a long and tragic marriage. Lu Xun was in despair; it affected his thoughts and his dreams of the future. His wife Zhu An suffered even more than Lu Xun. Lu Xun later said, “This is a gift from my mother, and I have to maintain it. There is no love between us. By sacrificing my entire life, I owe nothing to four thousand years of history.” Four thousand years is a very long time, while men only get to live a short few decades.

(Expert Commentary:) 鲁迅跟朱安的婚姻呢,后来他自己说的是:最苦的不是敌人射来的毒箭,而是自己亲人误给的毒药。误给他的毒药。他又爱他的母亲,不愿意伤他母亲的心,但是对朱安呢,他又无法接受。所以后来他跟许广平说:这不是我的媳妇,是母亲送给我的一个礼物,我只好养着她,爱情是谈不上的。

The fourth day after the wedding, Lu Xun, his brother Zhou Zuoren, and a few friends set out to Japan and didn’t return for three years. After years of study in Japan, Lu Xun left Tokyo for China in 1909. This is a photo of Lu Xun shortly after his return, dressed in a suit and tie, looking vigorous. However, two years after the 1911 Revolution, he showed up at Shaoxing Normal School looking like this. He hadn’t found his path until he wrote “A Madman’s Diary,” joined the New Youth magazine, and met a group of like-minded companions. Lu Xun finally arrived at a breakthrough point in his life.

“A black awning boat is moving slowly in the dusk. It is wet and cold in deep winter. A chilly wind sweeps across the sad and gloomy heart of a traveling man.” A year later, in the novel “Hometown,” Lu Xun revealed his feelings: “The old house is drifting away from me, and so are the landscapes from home. Yet I don’t feel many warm memories. I just feel there are invisible walls all around me, isolating and suffocating me.” “Hope is something both real and unreal, just like the path on the ground. There was no path, and it only takes shape as people walk on it.”

VI. The Rise of a Literary Titan and His Responsibility

After leaving his hometown, Lu Xun traveled to Beijing and worked as a professor at seven universities. His published works won him tremendous recognition. He wrote fiction, prose poems, and essays, and he did so not just in classical Chinese but in vernacular Chinese as well, making his work accessible to everyone. In 1919, Lu Xun bought a courtyard house in the old town area in Beijing. Lu Xun frequently had visitors at No. 11 Badaowan Alley, mostly well-known scholars. The Zhou brothers were very hospitable. One day, Zhou Zuoren invited Cai Yuanpei, who gave the brothers an offer to teach at Peking University. Since 1920, Lu Xun had been employed by seven colleges in Beijing to teach, including Peking University and Beijing Higher Normal College. His research on the history of Chinese novels was very popular in academia. In the literary world, his influence was well recognized. He was respected as a vital instructor in the Literature Research Association set up by Shen Yanbing (Mao Dun). He was also a mentor in the Qiancao literary association, Weiming Society, and the Chenzhong Society, seen as a leader in the literary world. He also established, with a few friends, the Threads of Talk magazine, the Weiming Society, and the Wilderness Society. Meanwhile, Lu Xun was passionate in artistic creation, with successive publication of his novels like “A Madman’s Diary” and “The True Story of Ah Q,” attracting great attention from readers in Beijing, Shanghai, and other places. “A Madman’s Diary” was even included in elementary school textbooks.

Chinese society was turbulent in the first two decades of the 20th century. Lu Xun’s novels in the 1920s cut open the grim reality of Chinese society like a scalpel.

(Someone said:) 有人说呃,《阿Q正传》同时也代表了人类的普遍特点。所以这的确是一个在世界史上具有重要意义的文学典型。他实际上他一生他创作了他写了300万字的作品,你发现都是前无古人的,都是新的啊。他没有被旧的文化所束缚,完全是呃一个新的、新诞生的这样的一种文化种类,一种文学种类。

The medium-length novel “The True Story of Ah Q” is his most famous work and the most frequently commented-on novel in the history of Chinese modern literature. It has been translated into many languages. The image of Ah Q was simmering in his mind for many years. Lu Xun said the reason why he engaged in literature was to wake up a sleeping public.

(Original quote:) “我要给阿Q立传……可是传的名目繁多……最后,只好从旧小说的一句所谓‘闲话休提,言归正传’里取出‘正传’这两个字来,便叫做《阿Q正传》。”

(Expert Commentary:) 《阿Q正传》它是一种隐喻啊。呃在这里边,通过一个人物形象,它折射出很丰富的我们民族生活的图景。我觉得这一点,鲁迅为我们文学史、不仅为中国文学史也为世界文学史,贡献了一个奇特的典型的形象。

VII. Family Strife and Emotional Rebirth

In the summer of 1923, the atmosphere suddenly intensified in the courtyard house. A sudden incident occurred in the family; the two brothers turned against each other. It happened very fast. On July 14th, Lu Xun wrote in his diary: “From this day on, I will have my own meals in my own room.”

(Expert Commentary:) 家庭的变化对鲁迅的影响还是很大的,特别是他和他二弟周作人之间的这个矛盾啊。后来他们分道扬镳,这个对鲁迅刺激很大。他当时鲁迅就喝酒,喝了很多酒,就是感觉到非常的痛,很痛心弟弟就这样和自己就这种友情就没有了,兄弟之情就结束了。这个对鲁迅伤害很大。就作为长子来讲,他就像父亲一样掌管着这个家,就有很高的责任感。因此这种责任感呢也放大到社会上,在社会上他也是时刻的想着中国,想着中国的革命啊,中国人的解放。这应该是啊纠缠着鲁迅的一生的一个观念。兄弟失和是对他的一个极大的打击,也是他把他的文学作品推向极致、成熟的这样一个标志。但是在这之后,鲁迅又和许广平恋爱,又走出了这个极度失望和绝望的深渊,又恢复了他原来的那个状态。这实际上是一场爱情把他给拯救了。

In 1925, 45-year-old Lu Xun fell in love. The object of his affection was one of his students, and she was nearly 20 years younger than him. At the start, they wrote letters to each other discussing life and society. It was from those letters that love grew. Their love story began through the exchange of letters. A month later, Xu Guangping visited Lu Xun for the first time. She called it an “adventure.” In her eyes, Lu Xun’s study, which he named “the Tiger’s Tail,” was full of fantastic colors: “Sitting in that room with big glass windows, when the red lights are out, sometimes you hear the sound of rain, and sometimes catch a few glimpses of the serene moonlight. When the Chinese jujube bears fruit, just watch how its branches sway in a breeze, and the ripe fruit drops. Sounds of chickens are heard all the year round.”

After this visit, it seemed their letters began to indicate romantic affection. They not only talked about society and life but also teased and amused each other. After that day, Xu Guangping visited Lu Xun more frequently. This is a love letter; this is a book of love letters. Lu Xun was the first writer in Chinese history to publish his love letters, which involved some diminutive names and intimate conversations, but mostly dialogues about the past, present, and future of China between Lu Xun and his student. It seems the young woman’s love gave Lu Xun the great strength he needed to pull himself together out of the dark abyss. This passionate prose poem written by Xu Guangping is more like a declaration of love: “It might be an overreach, it might be an improper match. We might be of the same kind, or we might not. It might be legal, or it might not. These have nothing to do with us and nothing to do with you.”

On October 3, 1927, Lu Xun and Xu Guangping arrived in Shanghai. After five days, they moved into No. 23 Jingyun Lane in the Hongkou District. With the progress of the Northern Expedition, a movement to create a united country, China’s cultural center gradually shifted from the ancient capital of Beijing to Shanghai. With its strong international influences, Shanghai was like a big, bustling stage. Here was the birthplace of radical revolutionary writers and a stronghold of old-school literati. In the changing situations, Shanghai began to show its dazzling brilliance. Lu Xun spent the last decade of his life in this environment.

VIII. The Shanghai Decade: Battle, Friendship, and Warmth

In the lonely darkness, Lu Xun liked to talk with several young friends about society, life, and literature. From the mornings and afternoons, he unconsciously acted like a father. In these photos, we see lively and cozy scenes of Lu Xun and his friends like Rou Shi and Feng Xuefeng. These young men accompanied Lu Xun all the time, watching movies, swimming, or visiting art exhibitions. Yet their friendship was often overshadowed by the bloodiness of politics. In a few years, young leftist writer Rou Shi was shot dead. Lu Xun lamented in his poem: “Facing the execution of my young comrades, the pain is like being cut by a dozen knives, and all I can do is write a little poem.” He also witnessed the death of Yang Quan, director-general of the China League for Civil Rights, and deplored: “My tears dropped in the rain south of the Jiangnan for the valiant fighters.”

(Expert Commentary:) 他很有责任感。萧红萧军到上海的时候没有钱,他们跟鲁迅借钱,第一次见面,鲁迅就给他们一笔钱,让他们能够能够有暂时在上海能够安顿下来。就是这种责任感,这种父爱般的责任感啊,不仅在家庭里面,在他在左联时期,对的青年艺术家和文学家,都表现的淋漓尽致,很让人感动。就是他是呃很有爱意,很有暖意的一个人,有责任感的人。

On September 26, 1929, Xu Guangping was in a hospital about to give birth to her and Lu Xun’s baby. Lu Xun gently put a small pine bonsai next to her bedside table. For a whole day and a night, Lu Xun hardly left her. Lu Xun was excited to become a father. The second day, Xu Guangping came home from the hospital and found another delicate pine bonsai in their house. More to her surprise, Lu Xun had rearranged the furniture and cleaned up every corner following the nurse’s requirements; he usually paid little attention to such things. When a baby was born in Shanghai, Lu Xun named him Haiying, meaning “infant of Shanghai.” He said the name was just temporary and a child could change it after he grew up. The doctor suggested hiring a nurse, but Lu Xun insisted on taking care of the baby himself. Since the couple had no parenting experience, they carefully followed instruction books on parenting for everything from breastfeeding to giving the baby a bath. Still, the baby often felt hungry or cold. They had to seek the doctor’s advice and hire a nurse.

In Zhou Haiying’s memory, a typical day in the house begins like this: “Father often has to spend the whole afternoon with visiting guests. The conversations usually last a long time. I can hear the laughter, and sometimes I join them. I have no idea when the guests leave at night because I have already fallen asleep.” Late at night after Haiying fell asleep, Lu Xun wrote. In the light of a lamp, Xu Guangping would read newspapers or do handicrafts by his side. The days with Xu Guangping in Shanghai were the best time of his life other than his childhood. He once said to Xu Guangping, “I have to do something for China to live up to you.” Ten years after they met, in December of 1934, Lu Xun wrote a poem for Xu Guangping: “For ten years we have gone through difficulties and helped each other in danger. I hope this collection of paintings pleases your exhausted eyes, and we share sweetness and bitterness together.”

(Expert Commentary:) 所以在中国社会最黑暗最无望的时候,鲁迅先生的文字里面,你会感觉到他虽然他接受了那么多的黑暗啊,写了形形色色的丑陋的人物,他和现象界里面那些呃魑魅魍魉的那种搏斗啊,所表现出的毅然决然的精神,并没有感觉到他阴冷,而且感觉到他身上是有一种热流在里边。所以这个就是一种担当感。鲁迅先生他不仅像刚才说的,承担了家庭的义务,他也肩负起了社会的这个责任。鲁迅作为一个现代知识分子,体现了他的责任,体现了他的使命感,体现了他的情怀,是吧这个呢又是有非常值得宝贵、非常值得我们这个学习继承的东西。哎他对于社会、对于民族、对于国家、对于文化、对于学术、对于文学,他都有极强的那种使命感跟那个责任感。鲁迅的一生就是反抗绝望,反抗奴性,希望人从奴性的人成长为自觉的人,这是他最深的一个价值。鲁迅能够把他一个具体的、一个家族的一个经验,和这个中华民族的民族国家的在现代世界里面所遭受的那种遭遇,把这个东西啊就可以合到一起来表达。呃所以在鲁迅的创作里边哎,个人的经验、家族的经验,都不是仅仅属于个人和这个家庭的,他同时呢也是属于我们中华民族的,也是属于我们呃就是国家的一种集体的经验。在这个民族走向绝望、没有路可走的时候,他用自己的智慧,和自己的生命的这种热能,他抵抗黑暗而肉搏这个惨淡的暗夜。他用生命自身的燃烧,发出光热来照亮了周围的世界啊,使我们感到我们这个世界还没有完全的沦丧啊。所以他感召了很多青年人走上了这个思想解放和文化解放的道路。

IX. Final Days and an Immortal Monument

In 1936, Lu Xun was tired and aged. Although he was only 56 years old, his health was getting worse after a serious illness in May 1928. Lu Xun had been suffering from tuberculosis and pleurisy. He often had fevers and coughed. Initially, the symptoms could be controlled by medication, but eventually, it began to fail. In autumn 1934, his fever lasted a month. He became even thinner, making his cheekbones appear even higher. His gums became distorted, and he couldn’t wear his dentures. He had to send for a doctor to make corrections. For most of the time, Lu Xun sat on a couch in solemn silence, his eyes closed, smoke from burning tobacco rolling up in his hand.

Over the following decade—the last decade of his life—Lu Xun used his writing to embrace his social responsibility as an intellectual, leaving an enduring literary monument for later generations. He numbed, comforted, and encouraged himself with work. He fought against death with work. He showed gratitude to his concerned friends and answered his enemies with work. “Act quickly” was one of his life principles in old age.

Early morning on October 18, 1936, Lu Xun had a sudden asthma attack. After fifty-six years of hardship, he had finally reached the end of his life. News of Lu Xun’s death spread quickly and shocked all of Shanghai. His son Haiying was only seven years old at the time. Several young artists like Cao Bai and Li Qun drew the last sketches of Lu Xun. He looked thin and tired. A Japanese dentist made a plaster death mask of Lu Xun with his beard and eyebrows. Ouyang Yuqian and a team from the Star Film Company made a documentary about his funeral. Over his body hung a pair of elegiac couplets written by Cai Yuanpei: “He had the strictest writings, a well-respected Chinese novelist; He had the heaviest last words: don’t be an empty-headed literature.”

A funeral procession of seven thousand people, led by Soong Ching-ling (Mme. Sun Yat-sen), accompanied his body to the Wanguo Cemetery. A portrait of him by Situ Qiao was held at the front. On their way, people sang a song specially written to commemorate him: “With a pen as sharp as a knife, you pierced through the face of old China; With a voice as sonorous as a tolling bell, you aroused slaves from their fond illusions.”